Investment Basics: Planning the Withdrawal of Your Retirement Assets

April 30, 2018

An efficient withdrawal strategy may be able to improve the overall performance and longevity of a retirement portfolio. Certain tactics for drawing cash from retirement assets may have more favorable tax implications for the investor. It is also possible to manage portfolio rebalancing in order to minimize transaction costs. Other factors that have a significant impact on withdrawal strategy include IRS required minimum distribution rules and large holdings of company stock in a qualified retirement plan.

You've worked long and hard to accumulate the assets that you are using to help finance your retirement. Now, it's time to start drawing down those assets. Exactly how you liquidate your assets will affect your tax and impact how long those assets last, so it pays to plan a withdrawal strategy that is efficient and maximizes the benefits of different types of investments.

The first step in planning your withdrawal strategy is to make a precise inventory of all the assets you have in your portfolio, paying particular attention to distinguish between taxable accounts, such as ordinary bank or brokerage accounts, and tax-deferred accounts such as 401(k), 403(b), and 457 plans, and IRAs. From this inventory, you can estimate how much cash you will receive from dividends, interest payments, redemptions, and distributions in the coming year. You can also assess how much you will need to hold in reserve in order to meet the associated federal and state tax obligations.

If your total net cash flow from the assets in your taxable accounts is strong enough to meet your budgeted cash needs for the year, you may consider yourself to be fortunate. You need not weigh the transaction costs of different asset sale strategies or consider the added income tax effects of withdrawing assets from employer-sponsored plans and IRAs. But if you do need to liquidate assets in order to meet your cash flow targets, then you should consider the pluses and minuses of each withdrawal strategy as outlined in the following savings withdrawal hierarchy.

As you consider these options, keep in mind that no single order can be right for every person and every situation. Among the additional issues you should consider when designing your withdrawal strategy are the management of portfolio risk, your tax bracket, and the cost basis of the investments. With that in mind, below is a high-level summary of guidelines for creating an appropriate strategy. Remember, this is a conceptual ranking. Your circumstances may require a different sequence, so be sure to obtain relevant financial advice before taking any action. Note, too, that estate tax considerations might have an impact on withdrawal priorities.

- Meet the rules for Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs). Owners of traditional IRAs and participants in 401(k), 403(b), and 457 plans must follow IRS schedules for the size and timing of their RMDs (see below). Those who fail to do so face a penalty tax equal to half of any required distribution that has not been taken by the applicable deadline.

- Sell losing positions in taxable accounts. If you have an investment that is worth less now than when you bought it, you may be able to create a tax deduction by selling that investment. This deduction can be used to offset any investment gains you realize. It can also be used to offset up to $3,000 in ordinary income ($1,500 for married individuals who file separate tax returns). Losses in excess of the limits can usually be carried forward for use in future years.

- Liquidate assets in taxable accounts that will generate neither capital gains nor losses. As you consider which assets to sell, keep your target asset allocation in mind. You may be able sell assets from a class that is currently overweighted in your portfolio. By focusing on reducing the overweighted class to restore balance, you can minimize net transaction costs.

- Realize gains from taxable accounts or withdraw assets from tax-deferred accounts to which nondeductible contributions have been made, such as after-tax contributions to a 401(k) plan. Which accounts to tap first within this category will depend on a number of factors, such as the cost basis relative to market value of the accounts to be liquidated and the tax characteristics of the assets in the taxable account. When liquidating taxable account assets, liquidate the holdings with long-term capital gains before those with short-term gains, and liquidate assets with the least unrealized gain first.

- Take additional distributions from tax-favored accounts. RMD rules, state tax treatment, and other features and characteristics of the different IRAs and employer-sponsored plans may make some accounts better candidates for earlier withdrawals. For instance, withdrawals from a traditional IRA would usually precede withdrawals from a Roth IRA.

Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs)

For traditional IRAs and employer-sponsored retirement savings plans, individuals must begin taking required minimum distributions no later than April 1 following the year in which they turn 70½. RMDs from a 401(k) can be delayed until actual retirement if the plan participant continues to be employed by the plan sponsor and he or she does not own more than 5% of the company. The size of an RMD is determined by the account owner's age. An account owner with a spousal beneficiary who is more than 10 years younger can base required minimum distributions on their joint life expectancy.

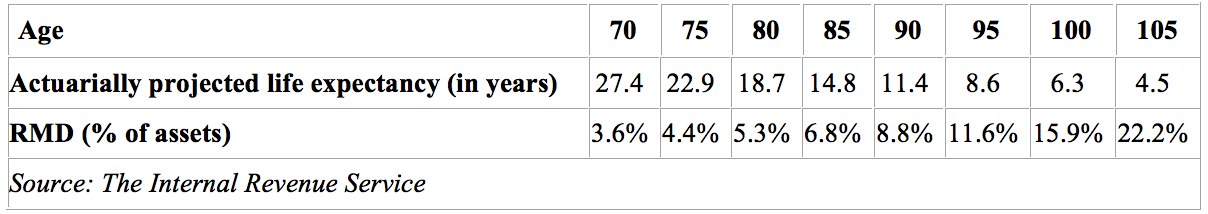

Estimating the Required Minimum Distribution

This is the most broadly applicable required minimum distribution table -- the Uniform Lifetime Table for unmarried owners, married owners whose spouses are not more than 10 years younger, and married owners whose spouses are not the sole beneficiaries of their accounts. Other tables apply in other situations.

A Potential Tax Benefit for Company Stock Held in a Retirement Plan

A Potential Tax Benefit for Company Stock Held in a Retirement Plan

For individuals who hold company stock in their 401(k) or other qualified retirement plan, the IRS offers certain tax advantages when withdrawing company stock from the plan. Rather than paying ordinary income tax on the entire amount of the withdrawal, you may elect to pay it on the original cost basis of the stock, assuming it was paid for in pre-tax dollars, then pay capital gains tax, usually at a lower rate, on the net unrealized appreciation when you eventually sell the shares.

Keep in mind that the IRS has exacting requirements for exploiting all of the tax management strategies discussed above and that tax laws are always subject to change. You should review your cash management plans with your tax and investment advisors before taking any specific action.